By Philip C. Winslow

Maternity clinic, Luena Central Hospital, Moxico Province, 1996. Photo credit: Philip C. Winslow

This is the first of three parts of a photo retrospective on three countries where Philip C. Winslow has worked since the mid-1990s: Angola, Sierra Leone, and Myanmar (Burma). All photos © Philip C. Winslow. Read part two and part three.

About thirty years ago when I was reporting the civil war in Angola, I heard about what in those days was called a leper colony, an isolated village in Angola’s northeast Lunda Sul province, near the Congo (then Zaire) border. Because all the villagers were thought to have leprosy—Hansen’s disease—both the Angolan Armed Forces (FAA) and UNITA rebels generally left the village alone rather than molesting and pillaging as they did everywhere else.

On the last leg of the journey, I was escorted by a Catholic nun who knew the villagers well. As she introduced me, she realized there was no word in Chokwe, the local language, for “journalist,” so she had to invent one. The description she came up with translated as “The white people who come and ask a lot of questions and then go away.” That day, I sat with the villagers in the shade of a large mango tree and listened to tales of survival, their anxieties and their faith during Angola’s long, grinding war. Reluctantly, I said goodbye to these gracious people and went away, back to Luanda on the Atlantic coast.

Looking back at Angola, Sierra Leone, and Myanmar is partly a late-in-life feeling that I owe people whose hardships and simple stories I chronicle before habitually leaving for somewhere else. My sense of benign debt follows the plea that I (and many reporters) frequently hear in troubled places: “We are alone. Please tell our stories.” And tell their stories I did. Some may find the notion that I “owe” highfalutin: it was a job, right? I did it and moved on to the other stories.

Memory and fondness (or loathing for the bad actors) are personal, and what we pick up along the way stays with us. Many of the people I interviewed and photographed are displaced or dead. I’ve had the privilege (and often the luck) of being able to go away, as the nun said. Most of these people did not. Or, they stayed put because they were home. Decades later, I still want their lives, or at least their faces, seen through other eyes and remembered. That’s all they ever asked of me.

I — ANGOLA: THE WORST WAR IN THE WORLD, 1994-1995, 1996

I reported from Angola 1993-1995 as the Southern Africa radio correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor, and later on my own. The war took a terrible toll on civilians, mostly through the use of landmines, but also through murder and various forms of coercion. For a time, the civil war, extravagantly fueled by the US and the Soviet Union, with help from South Africa and Cuba, was known as “the worst war in the world.” Although that title has passed to other conflicts, Angola’s forty-one years of war remain a distinct chapter in the annals of human destruction. My pictures show a large number of mine victims. They do not seem disproportionate: astonishing numbers of amputees—mutilados, as they were called in Portuguese—made their way along the dusty streets in every town and village I visited. Those who had lost a leg were the most visible because they were on crutches. Steel or aluminum shanks whose rubber tips had worn away clanked and scraped along the pavement, radiating pain upward through the shoulders and contorting what had been a symmetrical body. Those who had lost hands, arms or eyesight, or had perished, hovered like ghosts.

Maternity clinic, Luena Central Hospital, Moxico Province, 1996.

Kids outside the clinic, taking a break from a soccer game. They were highly skilled, using a crutch to whack a homemade rag ball. Most of the children had lost a leg to a mine, one to a gunshot wound.

Chisola Jorgeta Pezo, outside the abandoned Luena railway station where she and other displaced lived, in 1996. An antipersonnel mine blasted off her right foot on June 2, 1990, while she was searching for cassava. She was age thirty-six at the time, with three children. Infection later required an above-the-knee amputation.

Chisola and friends at Sunday church in Luena.

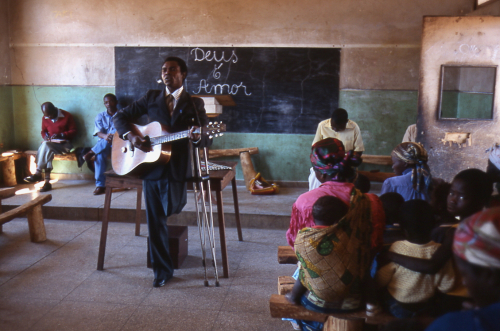

Henrique Ferreira Cardoso, Secretary, Cazombo Dos church. He lost a leg to a mine in 1984.

Tomas Jonas and Jodiki Cadita, his wife, Luena Central Hospital, 1996. He stepped on a mine near Luena airport.

João Adolfo, a firewood seller, Luena Central Hospital.

João Adolfo, a firewood seller, Luena Central Hospital.

Dr. Manuel Nzinga, director and chief surgeon, Luena Central Hospital director. Over the years, Nzinga and three other doctors amputated the limbs of hundreds of mine victims. The hospital had no anesthetic, soap or disinfectant. Patients had to supply their own food or medicine.

The Museum of Crutches, Luena Central Hospital, Moxico Province, 1996.

The Museum of Crutches, Luena Central Hospital, Moxico Province, 1996.

The Museum of Crutches, Luena Central Hospital, Moxico Province, 1996.

The Museum of Crutches, Luena Central Hospital, Moxico Province, 1996.

A woman grieves as the body of her mother, who just died of malaria, is taken to the hospital morgue, 1996.

A woman grieves as the body of her mother, who just died of malaria, is taken to the hospital morgue, 1996.

People living in the fuselage of a shot-down civilian airliner, Luena, Moxico Province, 1996.

The Benguela Railway yard at Luena, Moxico Province. Carriages on the cross-country railway provided some shelter for the displaced, 1996.

The Museum of the Revolution, at Luena, was repurposed as shelter for displaced Angolans.

Chisola Pezo and her daughter walking to the abandoned railway station, Luena, 1996.

A boy living with other displaced in the railway station, 1996.

A mine victim, walking in Luanda, 1994.

An Angola general visiting a soldier he described as a hero, in the central highlands, after a fierce battle with UNITA forces that left a field full of dead, 1995.

Francisco Muiengo, an engineer with the Mines Advisory Group, disarming a Romanian-made antipersonnel mine. A Russian anti-tank mine is visible underneath. Combatants often stacked the mines to maximize casualties.

Paulo Generoso probing around an antitank mine. Generoso, an engineer with the Mines Advisory Group, was Chisola Pezo’s brother.

Caxito camp feeding center for the war-displaced, north of Luanda, 1994.

An emergency feeding center, 1995. The message on the T-shirt was the election slogan of Angola’s ruling MPLA party.

A young Angolan soldier, sick with malaria, at a bush camp near Menongue, Cuando Cubango Province, 1995.

In Malanje, in the central highlands, a medic uses papaya pulp to treat a gunshot wound.

A family cooks in a ruined building in Kuíto, central Bié Province. UNITA besieged the city for nine months in 1993. More than 30,000 civilians were killed or died of starvation, burying the dead in back gardens. Bié Province vice-governor Estêvaõ Kossoma told me that for nearly a year, “The only song we heard was the sound of shelling. The only smell we knew was blood.”

Children in Kuíto hoping to sell a few potatoes and ground nuts during UNITA’s nine-month siege of the city.

A police officer with nothing to police, during the siege of Kuíto, 1994. A mine amputee stands behind him.

Abandoned rocket-propelled grenades, near Luena, 1996.

Abandoned rocket-propelled grenades, near Luena, 1996.

Near Canhengue village, Moxico Province. Landmines rendered large areas of land unusable.

Near Canhengue, Moxico Province. No path could be said to be safe.

Near Canhengue, Moxico Province. No path could be said to be safe.

Charcoal traders bicycle on a mined road near Canage, eastern Angola near the Zaire border.

Charcoal traders bicycle on a mined road near Canage, eastern Angola near the Zaire border.

The road was littered with the remains of blown-up trucks. About a dozen civilians were said to have been killed when this flatbed hit a mine.

The road was littered with the remains of blown-up trucks. About a dozen civilians were said to have been killed when this flatbed hit a mine.

The boot of a soldier who had been on one of the trucks.

The boot of a soldier who had been on one of the trucks.

Children in Moxico Province.

The Barracuda restaurant, a popular watering hole for foreigners and wealthy Angolans, near Luanda.

The Barracuda restaurant, a popular watering hole for foreigners and wealthy Angolans, near Luanda.

Outside the Barracuda, mine victims and former soldiers silently wait for handouts.

Wounded government soldiers, their families and a few journalists on a cargo flight from the highlands back to Luanda. In the forward hold lay a heap of broken weapons gathered from a battlefield. When the plane landed, the children on board inexplicably began whooping and smashing the broken weapons.

Wounded government soldiers, their families and a few journalists on a cargo flight from the highlands back to Luanda. In the forward hold lay a heap of broken weapons gathered from a battlefield. When the plane landed, the children on board inexplicably began whooping and smashing the broken weapons.

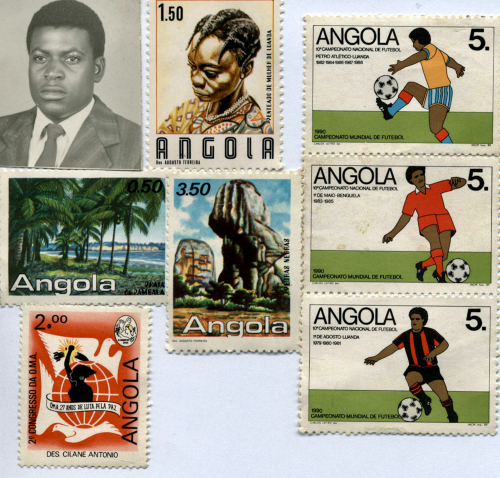

Tchau! So Long! This man, in his thirties, and I chatted at a ruined army barracks near Luena. As I left, he turned out his pockets and handed me the contents: a picture of himself in better days, some postage stamps, and the broken hand grip of an AK-47 rifle. I never knew his name.

Tchau! So Long! This man, in his thirties, and I chatted at a ruined army barracks near Luena. As I left, he turned out his pockets and handed me the contents: a picture of himself in better days, some postage stamps, and the broken hand grip of an AK-47 rifle. I never knew his name.

About the Author

Philip C. Winslow has been a journalist for fifty years; he has worked for the Christian Science Monitor, the Toronto Star, Maclean’s Magazine, ABC Radio News, CTV News, and CBC Radio. He also served in two United Nations peacekeeping missions and spent nearly three years living in the West Bank. He is the author of Victory For Us Is to See You Suffer and Sowing the Dragon’s Teeth.

![]() João Adolfo, a firewood seller, Luena Central Hospital.

João Adolfo, a firewood seller, Luena Central Hospital.![]() The Museum of Crutches, Luena Central Hospital, Moxico Province, 1996.

The Museum of Crutches, Luena Central Hospital, Moxico Province, 1996.![]() The Museum of Crutches, Luena Central Hospital, Moxico Province, 1996.

The Museum of Crutches, Luena Central Hospital, Moxico Province, 1996.![]() A woman grieves as the body of her mother, who just died of malaria, is taken to the hospital morgue, 1996.

A woman grieves as the body of her mother, who just died of malaria, is taken to the hospital morgue, 1996.![]() Abandoned rocket-propelled grenades, near Luena, 1996.

Abandoned rocket-propelled grenades, near Luena, 1996.![]() Near Canhengue, Moxico Province. No path could be said to be safe.

Near Canhengue, Moxico Province. No path could be said to be safe.![]() Charcoal traders bicycle on a mined road near Canage, eastern Angola near the Zaire border.

Charcoal traders bicycle on a mined road near Canage, eastern Angola near the Zaire border.![]() The road was littered with the remains of blown-up trucks. About a dozen civilians were said to have been killed when this flatbed hit a mine.

The road was littered with the remains of blown-up trucks. About a dozen civilians were said to have been killed when this flatbed hit a mine.![]() The boot of a soldier who had been on one of the trucks.

The boot of a soldier who had been on one of the trucks.![]() The Barracuda restaurant, a popular watering hole for foreigners and wealthy Angolans, near Luanda.

The Barracuda restaurant, a popular watering hole for foreigners and wealthy Angolans, near Luanda.![]() Wounded government soldiers, their families and a few journalists on a cargo flight from the highlands back to Luanda. In the forward hold lay a heap of broken weapons gathered from a battlefield. When the plane landed, the children on board inexplicably began whooping and smashing the broken weapons.

Wounded government soldiers, their families and a few journalists on a cargo flight from the highlands back to Luanda. In the forward hold lay a heap of broken weapons gathered from a battlefield. When the plane landed, the children on board inexplicably began whooping and smashing the broken weapons.![]() Tchau! So Long! This man, in his thirties, and I chatted at a ruined army barracks near Luena. As I left, he turned out his pockets and handed me the contents: a picture of himself in better days, some postage stamps, and the broken hand grip of an AK-47 rifle. I never knew his name.

Tchau! So Long! This man, in his thirties, and I chatted at a ruined army barracks near Luena. As I left, he turned out his pockets and handed me the contents: a picture of himself in better days, some postage stamps, and the broken hand grip of an AK-47 rifle. I never knew his name.

Leave a comment